The Official Enemy Territory Top Songs of 2025

Fuck it we’re doing listicles now. I’m gonna talk about my favorite songs. Here’s the rules:

- The list is no particular ranking.

- Only one song per album.

- The song didn’t need to release this year but this had to have been the year that I became obsessed with it.

- I’m not a music journalist and will not attempt to speak objectively, but I’ll try really hard to explain why I love all of these songs.

- I will probably break all of these rules before we’re done.

Alright let’s get goin.

Cameron Winter - Love Takes Miles

I often find that my all-time favorite songs are the ones that I hate the first time I hear them. Maybe “hate” is a strong word, but my favorite stuff is often the stuff that I don’t immediately understand how to engage with. Songs that present me with a brand-new idea and ask me to stretch my brain in unfamiliar ways. I’ve learned that if I put in the extra work to see that vision, it tends to pay off. I’ll be rewarded with a feeling or an insight or a way of approaching music that I would’ve been incapable of if I hadn’t made the attempt. Some songs will really ask you to put in the legwork, and this one takes quite a bit.

The first time I threw this song on in December of last year (sue me), I was expecting 3D Country Geese. Maybe sad acoustic Geese, something that would have a throughline to the band I’d seen open up for King Gizzard. This wasn’t that. Heavy Metal was a sprawling and mind-bending collection of recordings where Cameron Winter croaks and wails over his piano keys. It was an album that left me disoriented and a little nervous, but still curious. I was beginning to suspect that this was one of those times where I’d need to dig a little deeper.

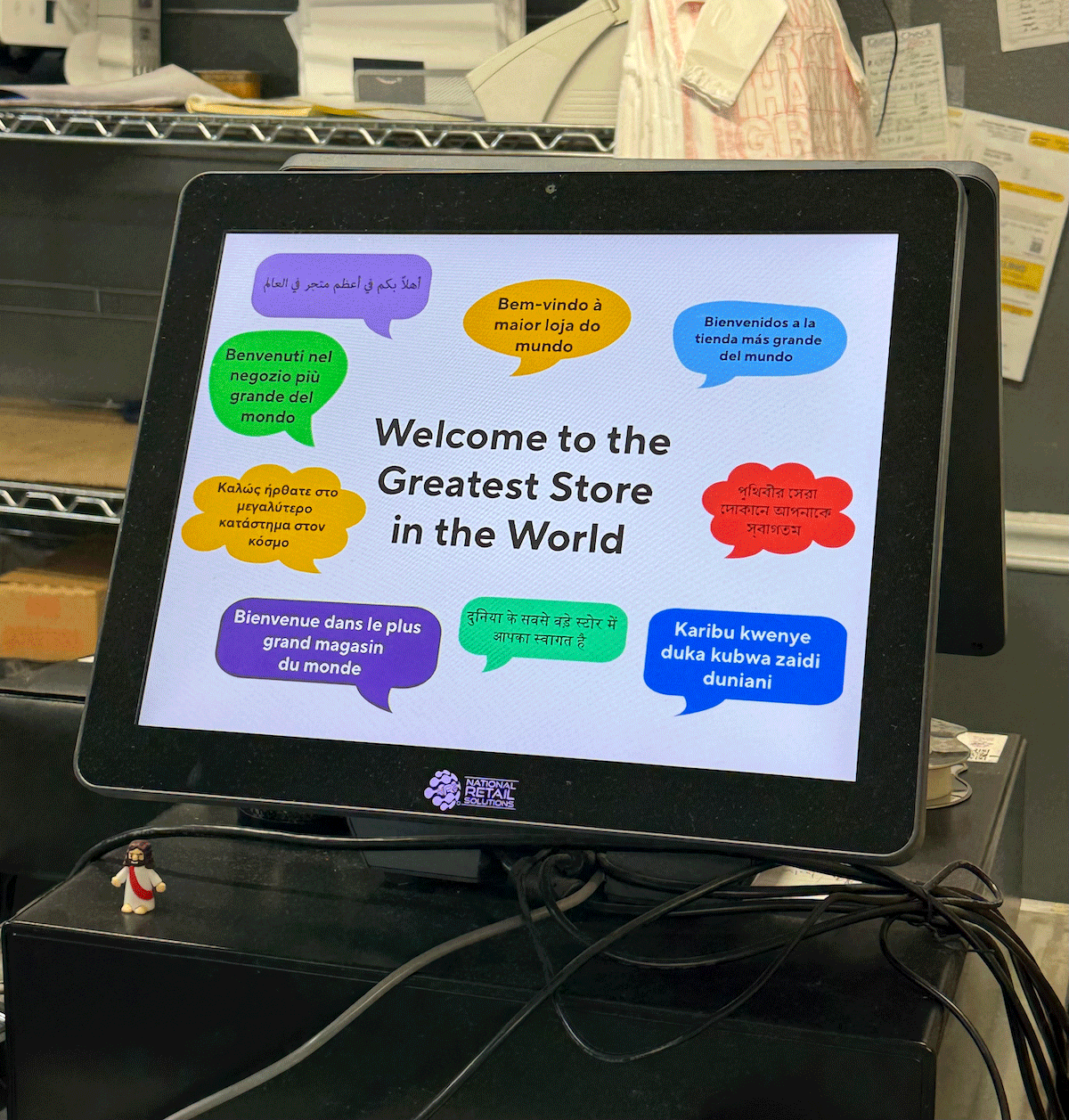

Deeper I dug. For six weeks I gradually came around to more songs on Heavy Metal. Adjusting my expectations and trying to find the right way to look the record in the eyes. My understanding slowly grew until, all at once, it all clicked. The first time I heard Love Takes Miles and understood it was in a Wal-Mart in Florence, Kentucky, on a freezing day in late January. I ended up walking laps around that store while Heavy Metal revealed itself to me, awestruck and excited and devastated all at once.

If Cameron Winter is the next great Gen-Z rock star on Getting Killed, Heavy Metal takes place after he’s drunkenly wandered off stage and over to the piano with a lump in his throat. There are some things that rock n’ roll isn’t suited for. It’s the closest thing you can get to baring your soul when you can never quite make eye contact because your fringe is in your face. He isn’t detached, but he’s abstract. The instrumentals don’t make any sense, the lyrics are slapstick and absurd, he’s singing like he’s trying to expel some evil that lives in his chest. This approach runs the risk of making something unlistenable, but he ends up somewhere breathtakingly poignant and sincere. He’s created a new musical plane that is never going to make sense the first time you try to stand on it.

It’s an album of standouts, but Love Takes Miles has to be the one that goes on the list. It’s not as much of a love song as it is a song about the concept of love. Exploring a feeling that will strike without notice, “Something will take you by your pants, and swing you over its head and kick you back and forth,” but requires more than just that initial impact for it to blossom into something valuable. Being in love is hard work; you have to be willing to get knocked around and go the distance for a love to really be worth anything. In other words, “You better start a-walkin, babe.”

Sonically, he starts out avoiding eye contact. A murky and wistful first verse that gives way to a chorus that finds Cameron sitting up straight and outwardly yearning. The song bubbling back down before building into a monumental second chorus and outro that are too bright to look directly at, overwhelming and life-affirming in the way only love can be. His delivery ranges from a tepid mumble to a full throated belt as the love that he was nervous to engage with manages to overtake him, screaming to the heavens that “What I want is on my mind.”

Loving a song and loving a person aren’t the same thing, but similar principles can apply. This song ended up being there for me at every emotional twist and turn this year. I walked with it as a companion on good and bad days, in yearning and depression. This kind of connection with a piece of music isn’t something that you find often, and it isn’t something that happens immediately. It was sent down from the sun, it swung me over its head. I found new things to love about it all year long. But I never would’ve experienced any of it if I hadn’t put in the miles.

Geese - Getting Killed

My favorite thing about the Geese album is how it makes you want to run through a wall. Momentum is something that I’ve experimented with quite a bit this year, and nothing could consistently launch me into a creative frenzy quite like Getting Killed. The album has the most thematically appropriate aesthetics of anything released in 2025, as an undeniable central theme of this year was getting quickly, violently, and unceremoniously fucking killed. When they revealed the album cover and it was just Emily Green pointing a gigantic revolver at the camera, I knew I was in for something very special.

Nearly impossible to pick just one song from this album (and I technically didn’t), but the title track has to be the one. It has the most abrasive start: A fucked up drum pattern and an incessant yelling? Chanting? over a crunched up guitar. They momentarily relent as the verse begins, but only to embark on a slow build into something frantic, paranoid, and violent. The song grows teeth, its veins start to pop out, and as soon as you start to flinch because you’re sure it’s about to pounce, it loses steam and sinks back to the ground. The drums quiet down and the guitar finds melancholy chords. What seems like it’s about to be a bloody spectacle of hyperviolence reveals itself to be a head-in-hands lamentation: “I’m getting killed by a pretty good life.”

That’s why it’s the one on the list. It’s a place that I found myself quite a few times this year: gritting my teeth and slamming on the gas, exerting every single ounce of my energy just to end up pathetic. Defeated by nothing in particular. Killed by my pretty good life.

Wednesday - Townies

I was tempted to give this spot to Elderberry Wine, since that was definitely the song of the summer, but I think there’s more to say about Townies.

There’s more to say because this might be the quintessential Wednesday song. It’s the perfect distillation of the sound that Karly Hartzman has been fine-tuning for years: A sweet, head-nodding country tune that’s ripped to shreds by a lightning-bolt riff, combining something heavy and something folksy so seamlessly that it never occurs to a listener that there would typically be a juxtaposition between the two. That’s what’s great about this song; the two things work together and are the same; they’re the simple frustration of living in small-town America.

For my money, Karly is the best lyricist going right now. This mix of carhartt-grit and eardrum-splitting shoegaze is accompanied by a lyrical account of what it feels like to catch up with the people you went to high school with. The way that the naive, youthful dynamics and scandals are temporarily resurrected in your psyche. She describes it as being surrounded by their ghosts. Even though I’m still a townie by the technical definition of the term, 2025 was the first year that I spent more time with my new, compatible adult friends than the aimless hometown crowd that I really only know through circumstance. Those encounters with my day 1’s being fewer and farther between allowed me to really relish in the absurdity of those relationships and allowed this song to feel more and more applicable to my own life. Thinking about a guy that you only really hung out with because he knew where to get drugs, questioning why he did something fucked up to you at age 16, wondering how someone could ever be so emotionally stunted and uncaring, ultimately coming to the conclusion that the illogical small-mindedness is nothing more than “You were sixteen and bored and drunk, and they're just townies.”

Sun Kil Moon - Space Travel is Boring

Every year without fail, I end up with a security blanket song to keep me company when times get tough. This year it was Mark Kozelek’s cover of Space Travel is Boring. He takes a frantic and ragged little song about getting bored while you’re flying to the moon—effectively a post-credits sequence on the first Modest Mouse album—and reworks it into something emotionally resonant that brings forward the loneliness and hardship depicted in the lyrics. His guitar rocks you back and forth and the refrain at the end becomes increasingly desperate and downtrodden. I’d wake up with the chords playing in my head and then ruin my day by playing it first thing in the morning. It’s not that this song was a particular comfort exactly, but when I was trudging through the part of the year that’s especially lonely and grey, it was meeting me exactly where I was at.

Addison Rae - Fame Is A Gun

There are few things that I love more than a song that can take my preconceived musical biases and smash them into pieces while I watch in horror. Addison Rae did that to me more than anyone this year, but I had a lot of fun in the process.

Try as I may to be aware of my own cultural predispositions as a twentysomething white guy, I can still sometimes catch myself writing off a piece of art just because I’m not in the group that it’s marketing itself towards. My teenage Redditor brain still tries to kick in and scoff when a former TikTok star puts out a pop album and everyone says it’s awesome, but I try my best to ignore that judgmental little voice. You miss out on a lot of good stuff when you decide you’re too smart for it or decide it’s “for girls” or whatever. If I missed out on this, it would’ve been a horrible shame.

Addison is fascinating. It’s forward thinking, honest in a way that catches you off guard, nostalgic but never derivative, silly but never empty, and so much fun. Fame is a Gun is one of the moments that best encapsulates these aspects: Uptempo synthpop that’s a little dark and a little sexy with an earworm chorus and perfect aesthetic sensibility. A red-blooded pop song to its core.

I chose this song because it was the source of one of the most humbling moments on my journey to becoming an Addison Rae fan: the realization that there’s a really salient metaphor at the lyrical core of this song. She depicts her public image, her fame, as the most imposing and threatening physical object imaginable: a gun pointed straight at her. But she’s not scared. She’s staring down the barrel of her critics and the public, daring them to define her and put her in a box. She establishes the destructive power of the object in front of her, and then she snatches it. And she’s waving it around the room. She fucking loves being famous, and she’s gonna use the power of this weapon to shoot through anybody that’s standing between her and the “glamorous life.”

This ends up being a good analogue of Addison Rae as I’ve come to understand her. A southern girl who liked to dance, arbitrarily plucked from the crowd by the algorithm of the dancing app that was sweeping the nation, thrust into a new and volatile type of fame where nobody knew her shelf life. But she’s an opportunist, and she’s smarter than the public would have you believe. She could see that TikTok virality wasn’t sustainable, so she used all of the new resources at her disposal to pivot. Surrounding herself with the people currently making the coolest stuff, learning and collaborating and establishing herself as more than a vapid influencer. To me, Addison (the album) is the sound of Addison (the person) using the full power of the fame that she was circumstantially awarded to create something undeniable, something that will stick with people and cement her as a major player in the pop scene. Proof that she’s not her TikTok contemporaries and she doesn’t plan on fading away. She’s shooting through everybody, because she fucking loves being famous.

Alex G - Real Thing

This was another security blanket song, but this time it was a comforting presence. It’s easy to take for granted how lucky I am to be alive while Alex G is consistently releasing his trademark fucked-up folk songs and bedroom ballads, so this is me enshrining my appreciation onto my blog forever.

As he gets older and leans farther into Americana, so do I, so even if Real Thing doesn’t have as much edge or angst as an older Alex G hit, it’s got things going for it that Sarah and Mary don’t. It’s one of those songs that lets me unclench my jaw. It manages to feel like somewhere I’ve been before, somebody’s back porch maybe. Familiar, comfortable, still steeped in that classic Alex G weirdness. We ought to tell him thank you more often.

Korea Girl - Reunion

In August, I went to Chicago by myself. In my experience, solo trips can go one of two ways:

(1) A carefree and curious exploration of a new place, never weighed down by time constraints or obligations or others’ expectations or fellow travelers’ needs to pee/eat/rest. Some of the best weekends of my life have been spent at my own pace in cheap hotels.

Or, (2) Lonely, boring, anxious, pointless. On a bad solo trip, if I end up overwhelmed or endlessly tracing a negative train of thought, I’ll get stuck in that headspace without companions to help me snap out of it. Or maybe I’ll see something great that will just make me wish that one of my friends was there to experience it with me. These trips end up feeling like a waste of time and money and effort, since I can be sullen and lonely in my bedroom for free.

Despite my best intentions, my Chicago trip was leaning heavily into category (2), and my descent into unpleasantry showed no signs of stopping. My tire had gone flat, I got pulled over, I had to try to navigate rush hour Chicago in a 2004 Toyota Corolla that couldn’t really stop or go, and despite me having finally arrived at the main event of my trip (King Gizzard with the Chicago Philharmonic Orchestra), the horrors did not pay off or cease. It was like 100 degrees, the sound system at the venue didn’t work so I could not hear the band, and the tickets I bought turned out to have a completely obstructed view, so I couldn’t see them either. Shit was fucked up. I drank a bunch of Trader Joe’s beer in my hotel room and watched South Park until I fell asleep.

I woke up feeling beat down. I had to bring my car to a tire shop, which ate most of my morning, so I didn’t even get to head downtown for exploration and fun until like 2pm. My hotel was far, so I boarded an empty car at the very last stop on the Blue Line (or the very first stop, if you’re an optimist) and prepared for an hour of being sweaty and pissed the fuck off on the train. That plan was cut short by this song (Reunion by Korea Girl, in case you forgot that this was a listicle) playing in the background of a TikTok.

Sometimes I’ll hear something that immediately lodges itself into the folds of my brain—something that I’m shocked to have never encountered and feels too good to be true. This was one of those times. It felt like a song that I should’ve heard before, maybe an indie rock classic that had evaded me for years. But no, it was the product of a short-lived Bay Area band that dissolved before they had a chance to make it big. I was enthralled.

This song, in that warm train car, instantly took an eraser to my long list of complaints and inconveniences. It’s simple and timeless indie rock, unpolished and easygoing. A cute account of the horrors of an impending high school reunion (thematically similar to Townies, now that I’m writing it down). But this was less about the lyrics for me in that moment; it was just something that managed to strike me exactly when I needed it. A song that encouraged staring wistfully out the window and humming along. I turned on the compilation of Korea Girl’s complete discography and allowed myself to exist in its upbeat lo-fi 1997 world until the train spit me out downtown, spiritually healed and ready to explore. And then I got a hot dog and ate it by the bean. Viva Illinois.

Sun Kil Moon - Ben’s My Friend

My Blue Line-indie rock grounding experience was the perspective shift that I needed to enjoy my next couple days in northern Illinois. Very soon I found myself in proper category (1) solo trip mode, wandering directionless around the Chicago Loop, admiring the buildings and people and details. I didn’t really even do anything of much substance that day. I traipsed from the bean to the art museum, wandered around until my phone was about to die. I started walking west through the sea of fast-walking Chicago pedestrians until I found a store that would sell me a phone charger. Four more blocks to the library where I charged my phone amongst my fellow Illinoisans without access to a private power outlet. Half an hour and an Italian beef later and I was on the train up to Lincoln Park for some more walking and a short stop at a card shop. I had successfully become immersed in my surroundings, no longer fighting my way up through the pile of minor inconveniences that had accumulated on top of me the day prior. I was determined to find wonder and joy in this city. Just me and my sweat and my jeans and my headphones. Did I mention it was the hottest day of the year?

It was sunset while I rode the Blue Line back to its northernmost point. One of those long August sunsets that feels like it lasts two hours. The sun fell lower and the other passengers all filtered out until it was dark and I was alone on the train, exhausted from the heat and my undirected marathon. That’s the kind of alone time that will melt your hardheaded sense of exploration into a glassy-eyed melancholy. Nothing visible out the window, no public transit strangers to wonder about or fall in love with or be afraid of. No option but to reflect. I was so far from home, so far from any of my friends or anything that felt consequential to me. I couldn’t decide if that was refreshing or if it was alienating to the point of crushing, but I didn’t get time to come to a conclusion. The train was at the end of the line.

I got off in a quiet neighborhood called Wilmette. Not a typical densely packed packed Chicago neighborhood, but not suburbia. It was all beautiful single-family homes with big yards and old streetlights with dim incandescent bulbs. I opened my Lyft app to take me back to the horrible office park that housed my hotel, but I noticed something I hadn’t seen when I’d set off earlier that afternoon. I was half a mile from a beach. The image of a dramatic coming-of-age beach moment to end my night of adventure was too good to pass up, so I kicked my legs back into gear and hit the sidewalk.

This walk was different. I was the only person on the street, looking into giant windows and activating motion sensor lights. It was far enough outside of the city that you could almost make out a few stars, unless those were just planes that I wasn’t looking hard enough at. This walk would’ve been a deal breaker on any trip besides a type (1) solo excursion. I can’t imagine walking ten miles through Chicago all day with a companion and then getting off the train to suggest a 9pm hike to see the same Great Lake we’d seen that afternoon. But the part of my brain that’s still 17 and still has the patience for melodrama was in charge, and there was nobody to be annoyed with but myself. After a good 15 minutes of walkin’, I cut through a little patch of woods and emerged in the parking lot of the beach, where a guy on a four wheeler looked confused by my arrival. I’d kind of anticipated that, since it became clear to me on my walk that this was quite the affluent neighborhood and they probably weren’t accustomed to tired, shaggy-haired guys with big jeans lumbering around at night. That kind of activity was reserved for their neighbors to the south. Regardless, I’d made it. Time to walk around the big wall that hid the beach from view and have my grand moment of reflection that I’d walked so far to earn.

Just kidding. I got like ten feet away from the big wall before a slavic-sounding guy who kept calling me “bro” pointed his flashlight at me and yelled that the beach had been closed for an hour. Despite my protests that “The sign said the park closes at 10,” he would not relent, so I sat on the sandy curb under a street light and called my Lyft. Fitting for the climax of my off-kilter trip to be just as mundane as the rest of it. The final destination of my adventure to nowhere: nondescript pavement under the gaze of a beach cop in a high-vis vest. What a romantic life. My Lyft arrived and I hopped in, sweaty and spent. I got comfortable, and I cannot for the life of me remember what inspired me to do this, but I put on a song I’d never heard before.

Ben’s My Friend took my breath away. It’s a fairly barebones folk-rock tune with Mark Kozelek’s trademark nylon strings and a drum kit. It was the first time I’d actually ever heard his lyrics, since all of the Sun Kil Moon that I’d heard up to that point were Modest Mouse covers. It shifted things around in my brain. He’s barely even singing, he’s just sort of rhythmically and desperately speaking as he opens on the date (August 3rd) and the fact that it’d been a “pretty slow and uneventful summer.” He goes on to describe a mundane day: He goes shopping with his girlfriend and they eat lunch. He calls his parents and his sister; he’s worried about his mom’s health. His mind wanders to the Postal Service concert he’d attended a few nights before, leading to a reflection on his trajectory as an artist and comparing it to his friend Ben Gibbard. It feels more like journalism than poetry, just a flat-out no-frills documentary of a day in his life. There’s nothing I loved more in 2025 than a journalistic exploration of something mundane. The concept of representing the real world through your own unique lens, allowing others to see what life is like through your eyes. That was the most inspiring thing in the world to me, so I loved this. Gradually, a saxophone rips through the acoustic guitar and the whole thing builds into a pretty triumphant moment where Mark sets his insecurities aside and expresses gratitude for the life he gets to lead. He may not be Ben Gibbard, but he still gets to write his songs and document his life. Every time I hear that saxophone solo I’m back in the backseat of that Lyft, watching the headlights pass and being mystified at the realization that you’re allowed to just write about whatever. Mark had a boring and off-kilter day just like me. And now I’m documenting mine just like him.

Wilco - Spiders (Kidsmoke) [Live in Chicago, May 2005]

No song made me want to be in a band more than this one. An 11-minute krautrock nightmare that feels like it might never end. It’d be overwhelming if it weren’t for the atom bomb that is the chorus. Is it a chorus if there’s no lyrics? Maybe we’ll call it an interlude section. The part where they stop noodling and hit the chords really hard. It’s gotta feel so sick to play a song that’s this long and this weird to a crowd that’s eating it up instead of a crowd that’s just enduring it. This is the song they used in that panic attack episode of The Bear where they left online ordering on overnight and Sydney stabs Richie in the ass. Shit is awesome, I love rock and roll and I love Wilco.

Colin Miller - Cadillac

An unexpected alt-country gem from MJ Lenderman’s drummer. It’s not particularly groundbreaking or emotional or anything, it’s just a solid ass song. His whole album is that way. It soundtracked many spring afternoons spent driving through the country. Sometimes you need some simple and comfortable guitar music to prop you up when you don’t have the energy to figure out something less accessible. Pairs well with a highway, sunlight through trees, a patio beer.

You could probably put this on at any kind of outdoor social gathering and nobody would be upset. They might even nod their heads.

Ninajirachi - iPod Touch

A buzzer beater entry to this list. I discovered this song while in the process of writing these little reviews, and boy am I glad that I did. I Love My Computer is a genius album. It’s an exploration of Nina’s relationship with her computer; tales of growing up online and the sort of uniquely modern situations that come with it—posting a thirst trap, accidentally seeing an ISIS beheading video, playing and learning on a cracked copy of FL Studio—all set to the hi-tech soundfont of the early 2010s. A sound I can best describe as “Nyan Cat (Dubstep Remix).”

She wears her influences on her sleeve, channeling Skrillex, deadmau5, early Diplo, and the other pioneers of the once-futuristic early 10’s EDM scene to create something nostalgic for the era of tech-optimism that never feels derivative or cheap, because the songs are about that era. These aesthetics, filtered through her Gen-Z hyperpop sensibilities, allow the songs to never linger or overstay their welcome, often transitioning track-to-track with zero momentum lost.

Even though she’s tackling the modern reality of being plugged-in from day one, she manages to avoid any large-scale buzzkill issues like phone addiction or brain atrophy. That’s because the songs aren’t about the computer and the internet and the societal implications of the tech age. The songs are about her. They’re about girlhood and creativity and loneliness and horniness, but they’re set in real life, where all of those things take place equally in reality and on the screen.

iPod Touch, my favorite on the album, finds Nina describing a song that she encountered online at age 12. Nobody else knows this song, which felt like a common occurrence in the days before the mass adoption of apps with music suggestion algorithms and TikTok sound virality. I’m sure the musical superiority complex that I had as a teenager was partially spawned from the deep-cut songs that I would collect from my little corners of the internet, songs that it felt like nobody knew but me. She lists off all of the things that her special song is associated with in her brain, her iPod touch with her Pikachu case that she’d hide under her pillow when she was up all night immersed in the wonders of the digital world. This is basically how I spent 6th grade. The whole thing is quick and punchy and catchy as hell, sharing sonic DNA with deadmau5’s Ghosts n Stuff but faster and more to the point.

It’s really fun to be old enough that there are artists my age making songs about the specific ways in which we grew up. There’s something baked into us regarding our relationship with technology that is hard to express. It’s just something you get, and Nina not only gets it, she gives a full account of it. It’s kinda like how old-school film directors can’t figure out how to tell a story with smartphones in it but Bo Burnham can come along with Eighth Grade and portray exactly what it’s like to be 13 and terrified of Instagram. (Not that she’s like Bo Burnham. That movie is really good, though.) It’s a concept album that she knocks out of the park and a song that feels like I lived it.

Geese - Trinidad (Live from the Basement)

“I can’t believe they all washed their hair for this.”

My most significant musical moment of 2025 happened in Nashville, Tennessee, In a 200-cap venue called the Blue Room, nine songs into a set of (at the time) unreleased Geese songs and b-side deep cuts. I was there with my buddy Drew, and this was just a show we’d decided to attend because it fit with our schedule. We were gearing up for Bonnaroo the next day, treating this show like an appetizer for a stacked Friday lineup that ended up getting flooded out and cancelled entirely. Little did I know that my appetizer was about to act as the official starting gun of a marathon of manic creative motivation that I would run for the rest of the year.

I’m getting ahead of myself. Back at the Blue Room, we were about three songs deep before Drew leaned over to me and said, “I guess they’re playing all new stuff.” And I said “I think they’ve got one called ‘There’s a Bomb in My Car,’” which we laughed off. I had seen a TikTok of Geese frontman Cameron Winter screaming that terroristic threat during a show a few weeks earlier, but I didn’t think it was a real song. He’s an unorthodox guy; I figured they were just deep in a jam or something and he felt the need to test the limits of the “clear and present danger” clause.

Geese was melting my face off. I had seen them three times prior as an opening band, but in this little room as the headline act they were really tearing into us, pulling out all the stops from their (then unannounced) Getting Killed. I was confused during the pause in Islands of Men. I was hypnotized by the rhythm section in Bow Down. I was making note that these new songs were more straightforward than the 3D Country songs I’d come to know. More effective in their goals and pointed straighter at you. Just when I’d started to lose track of how far we’d sonically travelled, they started up something meandering and menacing. Cameron leaning into his now-trademark Heavy Metal wail, telling us how he’d “tried so hard…” The beginning of Trinidad was lulling us into a daze, a daze that was actually a false sense of security.

I’ll never forget the sound that came from the crowd the first time Max Bassin smacked the shit out of his snare drum and Cameron screamed, “THERE’S A BOMB IN MY CAR.” A genuine gasp, a stunned laugh, a shriek of terror. Whatever snake-charming spell they’d put over us had been instantly shattered, everyone in the room thrown out of rhythm and our collective sway faltering. “Is he even allowed to say that?” I remember an uncontrollable grin forming on my face. My eyes lit up the way they do when I’m being a troublemaker. Music had never felt like this. By the last chorus we were all screaming it with him.

Trinidad instilled within me something that stayed with me long after I’d returned home from Tennessee and reentered my normal routine. It was a memory that I could tap into when things were feeling dull, when the world was beating me down and I needed reinforcements. This band had harnessed something important. They’d created an outlet for a generational angst and madness that had been brewing within me (and apparently a lot of people like me) since the beginning of the year.

I don’t really want to dive into the whole “America’s rapid slide into fascism” thing in my music review listicle, but the general state of things had been taking a pretty real toll on me. Every day felt like there was a machine generating new and creative ways to make the world horrible and meaningfully worse, and that our government was putting every resource imaginable into ensuring the machine could carry out its misdeeds. I was mad, I was scared, I was generally downtrodden. All of the laid-back, carefree music that I’d spent 2024 accumulating felt inappropriate. Who could relax and smell the breeze at a time like this? It felt pointless to even talk about, everybody knew what was going on. I had kind of retreated into myself. There weren’t many places I could occupy without encountering the horrors. It was that meme of the trolley problem with no lever and hundreds of people on the tracks. “You can only watch.”

I think this is a big part of why Trinidad, and then Taxes, and then 100 Horses, and then the entire Getting Killed collection of songs resonated not only with me, but with a lot of people my age. It’s a frantic, paranoid, freak-out of an album. It channels these palpable anxieties into beatdown instrumentals and lyrics so blunt and left-field that they knock you over before you ever see them coming. “There’s a bomb in my car.” “I’m getting killed.” “There are microphones under your bed.” It’s not Rage Against the Machine, though. It’s not overtly political or a call to arms or anything. The closest they get to that is telling the taxman that they’d rather be crucified than allow their money to fund the evils of the government. It’s less about life right now and more of an encapsulation of the feeling of life right now. There’s a tenderness right beneath the violence, hunched over in sorrow on Au Pays du Cocaine and Half Real. I could see myself in it and it gave me the answer to the question I didn’t realize I’d been asking all year: “What the hell do I do with all of these worries and fears?”

Use them as fuel. From the night of that concert to the night that Getting Killed released and every night since, I channeled every bit of excess energy I had into projects larger in scope than anything I’d taken on before. This album soundtracked 12 straight weekends of Bigfoot hunts, essay writing, and midwest travel. It had the ability to distill my negative spirals into raw energy. When I needed to lock in I’d put my head down and throw on 100 Horses. When I needed to get hyped up on a long drive I’d put on Long Island City and Kubrick stare out my windshield like a psychopath. It was playing during the most creative period of my adult life, one that is still ongoing, and one that officially started with the first chorus of Trinidad back in the middle of the summer.

Now you might be thinking, “That’s all nice and fine, Sam, but rule two of the listicle specifically states that this song cannot be on the list. You already did Getting Killed way back up there at the beginning.” To which I applaud your ability to remember something I said nearly 6,000 words ago, but I must point out that you’re mistaken.

This particular version of Trinidad, recorded live with the guy who usually does Radiohead’s engineering stuff, is not only not on the same album as Getting Killed, it’s not on an album at all. But it is the definitive version of the song, in this reviewer’s opinion. The studio one is good, but I feel like the experiments taken in the production suck the life out of it a little. This version, with the guitar solo swelling up and everybody trying to kill their instruments by the end, is not only more compelling and dynamic, but it’s much closer to the one that I was confronted with back at the Blue Room. It’s still capable of making me smile really big and puff my chest out, no matter how many times I’ve heard it now.

Honestly, this song is a great example of why I love music so much in the first place. You can read an author’s endless attempts to explain their point of view, you can watch a movie and come away with some of the themes or messages that the director wanted to get across, but music is different. It exists in some incorporeal space above the direct. It gets across feelings using sounds that it would take weeks to attempt to describe with words. Geese swing Trinidad and its six-word chorus around like a big club, and the impact of their attack is exactly the feeling they were trying to instill. Songs are the only artistic medium where someone can show you a piece and say “This is exactly how I’m feeling right now.” I think Jeff Tweedy said that. This list has really just been an opportunity for me to look back at my year and recount all of the times that I said, “This is exactly how I’m feeling right now.” The feeling in the case of this song being something close to “Pyrotechnic.” Or at least that’s as close as I can get with a word.

I don’t know if I can work in advertising anymore

The only reason that I’m so good at marketing and that it comes so naturally to me is because I am very afraid of it. I’ve now spent nearly the majority of my life on subconscious high alert, becoming increasingly aware of the million ways that the world around me is bent around persuading me to make certain decisions. I remember being 12 years old and attending my first Major League Baseball game and having one of those consciousness-activating moments in the stands, when I suddenly became aware that I couldn’t position my eyes anywhere without at least 3 brand names or logos permeating my vision. I could only either close my eyes or leave.

This perverse intrusion really bothered me, and it never really stopped bothering me. I coped in strange ways; I discovered the street artists of the 2000s and their crusade against billboards and the like; I joined them in their fight long after it had ended by beginning my stencil/sticker art project that has since become central to my identity (employing the same invasive marketing techniques (repetition, iconography, guerrilla marketing) to advertise nothing, the nothing being the point). I wouldn’t realize until later that the street artists had long since succumbed to the commercial black hole and that in my art project I was actually training to work at a marketing firm. It has always been, unfortunately, flowing through all my veins.

In the time since my great shock at the ballpark and now, ad technology has advanced in new and frightening ways. Mostly thanks to The Phone. It’s no longer enough to slip in 45 seconds of commercials between sections of your TV show; the machine is hungrier and more resourceful than that. Our best and brightest psychologists and engineers have been paid top dollar to construct the most guard-lowering, subconsciously intrusive messaging avenues that one can imagine. The visual real-estate Busch Stadium problem now happens constantly in your browser window. Trusted Internet personalities can be financially coerced into selling you something, taking advantage of the simulated relationship they‘ve cultivated with you. Entire farms of fake user accounts can be purchased and orchestrated to present a sense of grassroots urgency about a topic or idea. Internet platforms can be bought and manipulated to outright shift your perception of reality. Everything you see can only be met with intense scrutiny and paranoia. The practice of which has led to me becoming the sort of schizophrenic maniac that tries frantically to wake people up to the fact that Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift are not in fact in love, but are performing a high-stakes tap dance routine orchestrated by the marketing specialists at the National Football League and Universal Music Group. The only way I’ve been able to effectively cope with the horror is to know my enemy and try to understand their tactics.

I guess I should explain why it’s horror to me. Put simply: I do not like that there are systems in place that can alter the way that I think without my consent or knowledge. It feels unnatural and spiritually unclean. Something about the fact that my brain has been hacked into, by people who have worked very hard to find its exploits, twists my stomach up. It makes me feel small, it removes any agency that I thought I had. It makes me feel like I’m not in the driver’s seat. I really like to be in the driver’s seat.

It seems like becoming wise to the game would help me mentally deflect. Not the case. You can recognize that heroin is addictive and then still get addicted to heroin. I have started to feel a little bit frightened, however, that I might be a heroin dealer.

I don’t think that the marketing that I’m doing right now is particularly pervasive or evil. Sure, I’m greasing the wheels of capitalism and with that comes its attached sins but I’m not doing the thing that I feel particularly exploited by. But I finished my portfolio website last night, and I’m about to take a real, honest swing at applying at a bigger and better firm. And I think the work would be fulfilling to me, because (I did lie in my intro) paranoia isn’t the only reason I’m good at marketing. I love to observe and deconstruct and communicate and optimize. And I could make enough money to live very comfortably. But if I start offering my efforts to an organization with farther reach and a bigger machine, do I run the risk of turning some poor 13 year old at a ball game into a schizophrenic? Could I be dooming others to the paranoia that so often consumes me? Would it just happen to them anyway? Could I be more fulfilled digging ditches or putting together furniture if I still got to come home and play on the computer? Is this a real worry of mine, or is this some sort of moral posturing to cover up the fact that I’m still scared to progress in my life and career no matter how much preparation I’ve done? Who’s to say! Not me! But in my 20 minutes of ranting into my notes app I’ve accidentally stumbled into the truth behind my spiral so I think it’s time to sign off and take some deep breaths. I’ve got a mission to go on tomorrow.

The Best Billboard on the West Half of Interstate 24

Having spent the majority of my early 20’s alone in my car driving to and from every nearby major city, I get to know certain sections of the highway pretty well. My most traveled section, Interstate 24, is a big stretch of road that runs from southern Illinois all the way down to eastern Tennessee. I’ve only made it all the way down to east TN once, and even then I didn’t make it to the end of the road, so I’ve felt the need to reign in this essay’s hyperbolic title ever so slightly by specifying that I’m only talking about the western half of I-24, meaning the 192 mile section between Marion, Illinois and Nashville, Tennessee. I’ve been up and down this particular road in every sort of weather, every time of day, every state of mind that one can imagine. It isn’t a particularly interesting road. There are a few scenic sections and a few nasty congested sections and a (shockingly disappointing) lack of reputable establishments in which to take a highway poop (but it’s only about a 3 hour drive from one end to the other, so one can usually time their bowel movements or gastronomically triggering food intake strategically to avoid that problem altogether). It’s the road that takes me from my little hometown in Illinois to the bustling evangelical faux-country Hollywood of Nashville, TN. A city that, for all of its faults, has a fantastic and remarkably active music scene. Being a frequent patron of the arts (guy who goes to a lot of concerts), I’m down there a lot, and thereby often burning up the western half Interstate 24 with ever-increasing speed and familiarity.

Becoming familiar with an unremarkable road isn’t always the most enthralling experience. It’s more something that just sort of happens to you, like having fond memories of a really boring movie. Not because it’s any good, but because it was one of three DVDs you owned as a kid so it was just always on. I specify an unremarkable road because, hard to believe as it may be, there are interesting roads. An interesting road may have a lot of nice houses to covet and admire; There might be a particularly beautiful stretch that’s perfect for a sunset drive; I even know some interesting roads with stomach-dropping steep country hills that I’d take my high school girlfriend down at full speed to try to convince her that I was brave and spontaneous and fun. W-I-24 isn’t an interesting road, but in its mundanity emerges a lot of subtle character and depth that you just don’t get from the bombastic showings of our hall-of-fame interesting roads.

W-I-24’s almost-features and bits of stories are what elevates it to unremarkable road status, opposed to, god forbid, a boring road. This is a subtle but important distinction, as prolonged exposure to a boring road can tend to have some nasty side effects. (Drowsiness, disassociation, dry mouth, dread. Suicidal thoughts and actions may occur.) Boring roads are the kind they have in northern Indiana or up near Chicago, where there is absolutely fucking nothing going on for eye-wateringly long stretches of time. You don’t know how to properly appreciate a hill until they’re taken from you. It’s the kind of road that a third grader paints when they’re trying to learn about perspective. Just endless and straight and flat. Scenic in a photo, sure, but there are hardly things to understand or get to know. You’re left with your thoughts and the clouds and other people’s vanity license plates. Contact your doctor if you plan to traverse a boring road.

W-I-24 fits firmly in the middle of these two types of roads. You don’t spend the whole time glued to your surroundings, but it’s usually enough stimuli to fend off intrusive thoughts and prevent any mental spirals. The natural landscape of that part of the country helps us avoid boring territory, leaving some suspense as you round corners and top hills. There isn’t much to see atop those hills and around those corners, though. Too much to take in and we might lean towards interesting. There’s the forests to admire and the fields to gaze across and the occasional body of water to see for half a second before the brush returns, intermittently marked by little towns with copy/paste gas station/McDonald’s exits in case you need to pee or you’re about to starve to death. It ain’t half bad. Or maybe it’s exactly half bad.

On an unremarkable road, you’re allowed to enter a sort of meditative state (only accessible to me while I’m driving because that’s the only time I’m required by law to put my god damn phone down) where your brain becomes hypnotized by the hum of the tires and the subtle repetition of your surroundings. White lines in the center, empty blue attraction signs followed by big green exit signs, a run-down gas station on either side of you, trees, hills, repeat. Once your brain adjusts to this pattern, you run two risks: The risk of being consumed by intrusive and uncomfortable thoughts, and the risk of becoming bored-to-sleep and careening into a big green exit sign. You can prevent this by starting to notice things that aren’t The Pattern. On our beloved W-I-24 heading east, we cross a section of Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area that provides a couple minutes of awe and beauty (more than a couple if it’s under construction, which it always is.), we top some moderately scenic western-KY hills, and then hit Clarksville, TN, where things intensify traffic-wise enough to keep you busy until you hit Music City. The section between LBL and Clarksville is the most properly unremarkable, and that’s where you spend most of your time trying to find things that aren’t The Pattern.

I, as a traveller, (and as a member of a species that used to do this to find their way back to the cave they were hunter-gathering in) tend to subconsciously designate objects and buildings and signs on the side of the interstate as personal landmarks that let me know how far along I am on my journey. It feels distinct emotionally from simply looking at my GPS to see precisely how far away I am in miles, probably because it allows me to force a sort of highway-deja vu that lets me recount exactly how I was holding up emotionally the last time I made this drive and saw this landmark. Some of my favorite examples include:

- The Huck’s gas station in Beaver Dam, Kentucky (Western Kentucky Parkway) that is built into the center of the two interstate lanes, allowing drivers to exit left to get gas and pee without ever setting foot in Beaver Dam proper. Part of me thinks they should have built one thousand of these when they laid our great Interstate Highway System, but if that were the case I’d never have an excuse to spend 15 minutes in the mid-south’s most-forgotten roadside towns. So it’s probably fine that there’s just that one.

- The little green sign designating the SITE OF FATAL BUS CRASH, MAY 14, 1988 (I-71) that I pass on the way to Cincinnati that lets me know that I am within reasonable distance of seeing my friends and I can start to replace the meditative unremarkable-interstate-zen in my brain with excitement and anticipation (without ever thinking too much about just how fatal the bus crash must have been to warrant its own sign. It’s on the side of a pretty steep cliff, so signs are pointing to it being very fatal and very bad).

- The Jack Flash travel center with attached Subway in Farina, IL, (I-57) where I made the nice ladies who worked at the Subway laugh by trying to recreate the sandwich that I’d drunkenly constructed in Chicago the night before (my 23rd Birthday). It was such a ridiculous sandwich that I was having so much trouble trying to recall the composition of that the woman putting it together just started to laugh at me. I did not successfully reconstruct it but I was still a little hungover so what I ended up with was still effective and healing.

- What must be the world’s largest Confederate flag just outside of Paducah, KY, (I-24) complete with matching shrine to the Confederacy, all attached to a gigantic flea-market warehouse building. I mean, this is a car dealership sized flag. You can see it a mile down the road. It’s apparently privately owned by some “heritage not hate” ass organization and is technically protected under the first amendment so no matter how often the people of Paducah complain about the loud and unwelcoming tone-setter that might as well read “WHITES ONLY” just outside of town, the city is powerless to make them take it down. The city’s solution was to paint a mural onto the water tower that sits across the highway from the flag, featuring a black hand shaking a white hand in front of a big American flag next to the words “United we Stand.” Which I always think is a little bit funny because it doesn’t really do anything to meaningfully combat the enormous racist flag, but it does sort of put a little “Yeesh, sorry!” band-aid on it. The visual combination of hateful ignorance and half-assed opposition never fail to make it clear that I’ve almost made it back home.

The most common type of object that becomes a de-facto landmark is the mighty billboard. I’ve always admired a billboard. All-seeing and all-powerful, forcing its message onto the millions of puny pedestrians below who are too weak and feeble to resist the forceful injection of information. Billboards are a mostly dead marketing channel in 2025, since printing costs a lot and there’s no real way to measure impressions or clicks or referrals or any of the of great advertising metrics that keep our digital lives so full of relevant marketing. Most of the money in tactical advertising is in being able to tangibly prove that you really did place a client’s message in front of a specific amount of/group of people, and billboards don’t allow for that sort of proof. I guess there are estimations of how much vehicle traffic a certain section of the road might see on a given day, but even then there’s no way to measure how many of your new customers first heard about you through your billboard. Those people might not even realize it if they did. In that sense, it’s a beautiful sort of vibes-based advertising tool, and when I’m in office it will be one of the only ad mediums allowed to continue to exist.

Anyway, the result of billboards being mostly dead is that the only ones worth really investing in are the ones in large metropolitan areas where people are going to see them constantly. The billboards on unremarkable roads are either left vacant or doomed with the menial tasks of letting you know that there’s another Cracker Barrel coming up in 8 miles; that there’s a Pilot gas station or another McDonald’s. Stuff you would quickly become aware of anyway as soon as you saw one of their skyscraper-height signs peeking up over the trees. There’s no competition out there, it’s barely conscious communication. It feels a little bit like those companies are buying billboards out of courtesy. “This 54 year old road still tells you where to get a Big Mac the old fashioned way.” The big corporate chain billboards obviously aren’t the kind that become landmarks, since they lack the bite and exhilaration of advertising that needs to be creative. The really good billboards — the landmark kind — are the ones put up by local businesses who are clueless as to how to properly advertise a business. They are the best. On W-I-24 alone we have:

- A billboard for (what seems to be) a roofing company, featuring all six of (what one can presume to be) the owners’ kids standing in descending height order, diagonally holding up a sign that probably contains a cute pun or slogan but is rendered absolutely illegible by poor color and font choice. It ends up coming across as an advertisement for someone’s children and their varying heights. Hilarious.

- A double billboard (top and bottom sections combined for maximum billboard) for (what seems to be) a liquor store, featuring a stock photo of a bunch of ecstatic young people smiling and laughing in a semicircle, having what looks like a really fun party, with a big white box beneath them that contains italicized Times New Roman text reading “Nobody Likes a Quitter!” I cannot for the life of me figure out what message they could be trying to convey besides “KEEP DRINKING.” and it makes me laugh every single time.

- A positively baffling yellow billboard with big red text that says “WE UNDERSTOOD THE ASSIGNMENT.” above a little character that looks like Mario’s estranged cousin who really leaned into the whole Italian thing. No calls to action, no discernible branding of any type. Hilarious in its waste of visual real estate and company resources, whatever company it may be attached to. I eventually came to learn that the little Mario character is the new mascot of regional pizza buffet chain Pizza Inn. I remember their mascot being a little beady-eyed character with a pointy hat, so this new guy was a stranger to me, and I assume a stranger to the rest of the world. Combine his unfamiliarity with a nonsensical and outdated internet reference and it feels like the billboard equivalent of an AI-generated blue checkmark Twitter account trying to piece together an approximation of what a person would post, only blown up to 14’x48’ and placed on the side of the highway for all to see. Remarkable.

These are each hilarious in their own special ways, but they all emerge from the same spiritual place. In their badness and inefficacy they let slip the shiny veil of marketing; they let you in on the big secret: the secret that every billboard you see was actually designed by a human being with a computer and a job and a brain, and that this time their brains misfired to create something strange and off-putting enough that you, the viewer, are forced to ask “Who thought that was a good idea?” Thereby becoming suddenly conscious that someone had thought of it at all. They break the illusion that billboards just grow out of the ground, spawned by the roadside to impart their wisdom onto travelers. Peeling back that curtain is always a rush, it’s the same feeling as noticing that your teacher misspelled something on the board. It’s a little victory against something that seems impossibly more powerful than you. It’s an inkling that something that’s only ever presented as an institutional force might secretly be human. In our case, it’s a window that invites you to imagine a person, not so different from yourself, deciding that their billboard should say “Nobody Likes a Quitter,” typing it out, adding an exclamation point, and pressing send on that email. Terrible billboards are a little speck of humanity amongst a sea of messages that have successfully had their personhood ripped from them by corporate interests.

Terrible billboards aren’t the only kind of billboards with humanity, and they aren’t the only sort that become landmarks. Thus finally allowing us to arrive at the titular Greatest Billboard on W-I-24:

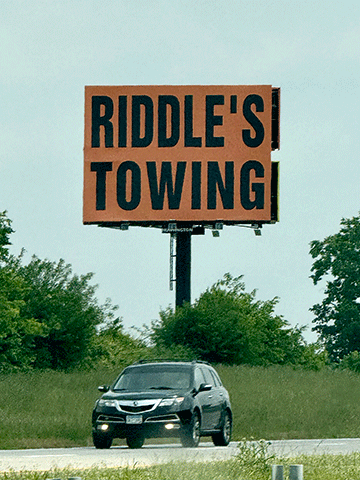

RIDDLE’S TOWING.

On the (notably uninteresting) section of I-24 that runs through an unincorporated territory called Gracey, Kentucky, heading East, there sits on the opposite roadside a billboard whose two back panels have been conjoined to form one enormous 28’x48’ orange sign, touting only two words in black Impact font: RIDDLE’S TOWING. Note the lack of a photo of a tow truck, the lack of eye-catching composition or font variation, the lack of an emotional appeal or a call to action or even a phone number to call. No URL, no fine print, no QR code, no little jokes, no tagline, just orange and black and RIDDLE’S TOWING. With its size and imposition and matter-of-factness it might as well read “RIDDLE’S TOWING. FUCK YOU.” It borders on the “CONSUME,”“OBEY” billboards in Carpenter’s They Live, but its earnest allows it to avoid becoming dystopian. It’s a piece of communication that respects its audience. RIDDLE’S TOWING knows that you don’t need to be sold on a towing company if you’re in unincorporated Kentucky and in need of a towing company, and it doesn’t patronize or try to convince you that it’s the choice for the job. It simply stands at attention, half a mile past mile marker 71, and lets its presence be known. It’s an honest, southern way to advertise.

RIDDLE’S TOWING not only respects its audience, it understands them in a deep and fundamental way. This sort of maximum-efficiency communication can only be achieved with a complete understanding of who you’re trying to speak to and how your message is going to come across. It understands the purpose of itself and strips away all fat. Imagine it: You’re barreling down W-I-24, reading license plates and billboards to stave off absolute boredom, rapidly approaching an enlightened highway-zen, when you’re abruptly snapped out of your trance by a POP and then a grinding sound that’s rapidly increasing in volume as your vehicle veers uncontrollably to the right. “Shit, did my tire just pop?” Once the initial shock wears off, you pull your poor, crippled car onto the side of the road and get out to investigate. Sure enough, shredded. Do you have a spare? Of course not, hypothetical You is a disaster. Even if you had a spare you wouldn’t know how to put it on. “What the hell do I do?!” you scream to the heavens. As you look upward (to see if God will respond), you see it. RIDDLE’S TOWING. [The lord’s trumpets sound] You proceed to do exactly what the billboard knows you’re gonna do, you type those two words into your phone and press on the little handset-shaped icon under the first Google result. Immediately, you’re rescued by one of the sweet old southern gentlemen who work for RIDDLE’S TOWING, and he makes sure you’re alright and offers you a blanket and a warm beverage in the cab of his tow truck while he provides you with the resources and next steps required to get back on the road in no time.*

*Some artistic liberties taken for the sake of example. Riddle’s towing is not a paid partner of Enemy Territory nor have I ever done business with them, however much I’d like to.

That might be a little fantastical but their sales pipeline is ingenious. They understand the fact that their ideal customer, someone in car-crash panic, does not need 3 bulleted reasons why RIDDLE’S is the premium towing experience. No customer will ever open their Phone app and type in a phone number, digit-by-digit, to make a distressed call for help. RIDDLE’S has seen how this situation plays out and they’ve adjusted their marketing accordingly. They knows that their name does all of the talking, and they just need their name in your brain. They’re brave enough to subvert and reject the traditional marketing conventions that our brains learn to tune out. A lesser company would have a worrywart that tries to make the case of “How will anybody know what we do or how to contact us?” to which RIDDLE’S TOWING once again replies, “FUCK YOU.” They’re brave enough to recognize the new social structure in which a modern driver is Googling stuff behind the wheel. They understand the idea of our iPhones being extensions of our bodies; our access to the hivemind and to all collected knowledge. This is the sort of bravery and mastery of advertising that you only usually get to see executed by the biggest and bravest agencies in the world’s metropolitan centers, but they’re doing it out in Kentucky, just past Cadiz. What really makes it the best, however, is that I truly believe this achievement to be unintentional.

To illustrate how this is even possible, I need you to once again peek behind the curtain and imagine the person whose job it was to design that billboard and send it out to for print. Who they must be and what their thought process must have been. We’ll start with what we know: We’re properly in the middle of nowhere Kentucky, halfway from Paducah to Nashville. Fields outnumber houses on this stretch of road 5:1. Red-State Heartland USA, where you can still sort of make an honest living by being the one guy in town with a tow truck. Even if RIDDLE’S has expanded past the Tow Mater model of doing business, it’s not likely that it’s a bigger operation than the Riddle family and a few good ‘ole boys with their tow trucks and a couple sheet metal buildings, the image of which doesn’t exactly financially lend itself to a partnership with a giant advertising firm, or a real marketing manager, or even really a marketing budget at all. My safe assumption being that the designer of this billboard probably doesn’t specialize in or even really care that much about being the person that designed this billboard. It was probably just something on a task list for them, between “ANTHONY CDL RENEWAL TRAINING” and “COKE MACHINE REFILLS.”

I like to imagine it went something like this: “Hey, we need to get the word out about RIDDLE’S TOWING. Boss gave us $800 to throw at a billboard.” To which our designer, resourceful and utilitarian, opens their work computer and types in “Busiest road near me.” Of course! Beloved Interstate 24. The next question, “How do you get the word out?” Answered with similar swiftness and certainty: “What color will get everyone’s attention? Traffic-cone orange. What font do we pick? The fattest one installed on my computer. What should the sign say? I was told to get the word out about RIDDLE’S TOWING, what else would the sign possibly say. Boom, done, onto the next thing.” In this point-and-shoot approach, they manage to effortlessly create something more effective than a seasoned marketer could ever dream of, because they didn’t think about it enough to make it bad. It’s dripping in small-town human ingenuity. They’d probably spray paint their name on the sign if that would’ve been easier.

This isn’t to say that the kind folks at RIDDLE’S don’t know what they’re doing. Invoking Tow Mater is not to imply that our new favorite towing company is run by backwater hicks that are too stupid to operate Adobe Illustrator. Creating a pretend office assistant’s task list is not to diminish the work that our hypothetical person does for their towing company. It’s to illustrate the real beauty of RIDDLE’S TOWING: unintentional, honest sincerety and simplicity.

Especially lately, the I find the world swirling around above my head. Too nonsensical and complicated to grasp at any of the spinning threads and put them in any sort of order. A tangled nightmare where any attempt at untangling an individual mental thread can only lead to an endless schizophrenic spiral of ever-increasing horror. I’d describe one here but I’d hate to kill the mood. This is just to say that I often feel, when trying to trace an idea about modern life or politics or technology to its logical conclusion, that I’ll be rendered paralyzed at the complexity and chaos of it all. It’ll start to get to you if you aren’t careful. On an uninteresting road, it’s lurking around every corner, waiting for the mental vacancy to appear. On a boring road it might as well be listed on the back of the box. WARNING: Your mind will run wild. Take caution.

Something I’ve become very interested in is the fact that, regardless if they realize it or not, everyone can feel this swirling, and that everyone copes with it in different ways. The most common way that we cope is by telling ourselves stories. This is the real reason that I love RIDDLE’S TOWING. The reason I point at it and holler “RIDDLE’S TOWIIIIING” when I pass through Gracey. Because, for a moment, without even realizing it, I get to indulge in my fantasy of a simple world. Where a business can operate in the most straightforward way imaginable. A world with no ulterior motives, where the signs on the road aren’t trying to get in my head and subconsciously infect my mind, but they’re instead opting to present their offering with honesty and integrity. A world where a caricature of a tow truck driver spent an afternoon fiddling around with Microsoft Paint. A story about a sign put up by the kinds of people I grew up around. Regular country folk, seemingly only concerned with getting in a hard day’s work and coming home to their families. A passing comfort on an unremarkable road.

This is, I cannot emphasize enough, a fantasy. It’s important to make that distinction, because the idea that there is some sort of ideal utopia in small town America where you can just offer a service without exploitation or residual victims is the kind of delusion that makes people think that capitalism is a beautiful and perfect mode of operation. Believing that the fantasy is real might make you inclined to protect it, and before you know it you’ll find yourself holding a protest sign outside of a Planned Parenthood or wearing a red hat. The world is never that simple, and the solution to the endless chaotic nightmare thoughts is not to try and create that simple, black and white world. You can find comfort in a dreamworld while still recognizing it for what it is. In my case, it’s something to occupy my mind for about forty seconds until I notice my next landmark, or a car with a funny bumper sticker, or some sort of roadside animal. And it’s an opportunity to exercise wonder about the mundane; To piece together a human story using only your context clues. It’s the most fun you can have in your life, flexing your imaginative muscles to try and explain the world around you. Letting yourself get a little silly with it. It’s certainly the only way to stay sane on the interstate.

And hey, maybe parts of my story are true! I’d like to hope so. Surely they picked the orange because it’s the road construction color. Imagine if it really was a guy with a big gut in overalls trying to use MS Paint. Maybe my next piece will be a journalistic deep dive into the real story of my favorite billboard. That’d be kind of fun. Until then, it can stay just a made-up story that I like to tell myself. One set on one of my favorite roads, where a nice guy doing honest business can provide help to a stranger in a time of crisis. Maybe one day it’ll be me.

Hamster Wheel

Lately I’ve been a hamster running really hard on my wheel. Endless motivation, endless speed. Nothing particularly ahead, just getting better and better at running on my wheel. This past weekend I fell off my wheel.

To be more specific, I found the upper limit of how hard and fast I’m capable of running on my wheel, and, importantly, how long I can run on my wheel without completely freaking out. I hit a sort of emotional snag three weeks ago, but I figured I could just use my newly learned momentum to propel myself directly and completely through it, gaining speed all the while. This was not the case. After effectively doubling my speed instead of confronting my feelings, my weak little hamster legs fully gave out on me. I face-planted and spun around vertically at supersonic speed. In my spinning out I threw up in four unique locations, cried in three, and gave serious thought to jumping off of one roof (but only because I knew I wouldn’t die and I thought it might make the other people on the roof laugh). I was then forcefully ejected from the wheel, flying through the air in a cartoon arc (complete with slide whistle) and hitting the ground on my side, legs still kicking but completely ineffective. I kicked and screamed until I finally got tired, gnashing my teeth and screeching or whatever noise hamsters make, being a little embarrassing and a little too candid about my feelings. Anything but working through what’s bothering me.

Laying on the ground next to my wheel, I was completely broken down. I'd been effectively paralyzed with anxiety, guilt, shame, panic, most of the negative emotions that I had managed to outrun while I was on my wheel. They’d been waiting for me to stop. For two full days I was in disrepair. My pistons wouldn’t fire correctly, my fuel injectors were bad. Something was very wrong. (Wait, wasn’t I doing a hamster analogy? What’s this car stuff? It’s fine, that went on a little too long anyway. And my writing’s allowed to be bad on here. The only way I can get good at it is by being bad first, fuck you.) In my broken down state, however, I was forced to sit and reflect. To take some real time and get to the root of the things that were scaring me so bad that I was running for my life.

Now I’m sat back upright. Not fully ready to take off again, but I’m starting to feel the wind in my sail. (Jesus what am I, a boat now? I’m really ruining the serious and vague nature of my little reflection with this side monologue. But some might say I ruined it when I went from hamster to car to boat. I’ll stop interrupting.) I’m off my wheel, and I could climb back on, but I’ve seen where that gets me. I think I might actually start covering some ground for a change. Maybe I’ll use my newfound love of running to actually chase after that cheese. Or, after that apple? Whatever hamsters actually eat.

Today I Bought a New Wallet

Today I bought a new wallet because the wallet I’ve been using for the past year and a half is too big and wide and the combination of its size and my gigantic curvaceous thighs and ass keeps causing me to rip my pants in the butt, right next to the back pocket where I keep my wallet. It also hurts to sit on for very long at all, which becomes a problem pretty quickly when you’re like me and your job is to sit at a desk and play on the computer and your favorite leisure activities are to sit in your car and drive for extended periods of time and to sit at a desk and play on the computer. It’s not a Big Wallet in the sense that there’s a ton of money in it either, I don’t carry cash, and if I did, I don’t think it’d be wise to carry enough to give me back problems. This wallet and myself just did not match, and after waiting entirely too long I’ve finally done something about it.

Today I bought a new wallet and in doing so I’m discarding one of the only remaining reminders of my first and only long-term adult relationship. I received my Big Wallet in 2023 as a Christmas gift from my now-ex girlfriend. I don’t remember what I got her for Christmas that year, but I vividly remember opening this wallet. I think if you you had slow-motion camera footage of the 0.2 seconds where I was opening my gift, you could watch my face start to contort, followed by a barely visible jolt going through my entire body that could only be properly described as my heart shattering a little, followed by my real emotions retreating behind a mask of A Guy That Really Liked This Wallet. The reason you could see my heart shatter was not because the wallet was a thoughtless, last minute gift of any sort. She was trying very, very hard to get me something that I would love and cherish, and that was exactly the problem. It was a fine gift. A nice, thoughtful gift even! My old wallet before the Big Wallet was one that I’d been using for the better part of 10 years. It was absolutely falling apart and the leather on the outside was scraped and gross and it was an all-around disaster. The one that she got me to replace it was a very nice Carhartt wallet, another detail of thoughtfulness because I was in a sort of workwear phase at the time, and I was always raving about my Carhartt jacket and my Carhartt pants.

This was, in fact, a good gift. So why did we watch my heart break on the high-speed camera earlier? In that moment, the wallet felt indicative of a feeling that had been creeping up on me for a while. A feeling that there was some sort of fundamental misunderstanding in my relationship, a feeling of a ticking clock where love used to be. The wallet felt representative of an eternal mediocrity that was headed straight for me, one where I lived in a grey apartment and then a grey house with two regular kids and got socks and a belt and a wallet every year for Christmas. A safe and predictable and good-enough life. And the shattering of my heart wasn’t only because I was coming to realize that we wanted very different lives for ourselves, but also because I felt really guilty for having such disdain for the ideal life of the person I cared about. What was I, some sort of narcissist that couldn’t even entertain the idea of a life wasn’t centered around ME and my own pursuits? I felt guilty for knowing deep down that I would be more satisfied with a life that involved a lot more risk and rambunctiousness and inquisition. And I was quietly gutted because I knew that she either didn't realize this yet, or was denying it too. There was a hopelessness in that realization and guilt that I was actively trying to keep at bay, and for 0.2 seconds the gift of that wallet allowed it to rise to the surface. Those feelings spawned a new hopelessness that I’m grappling with almost 2 full years later; the worry that any pursuit of long-term forever romance is doomed to the creeping death-sentence of Knowing. That there won’t be any inciting incidents, things will just erode over time. Even the most beautiful connections rendered pointless or even hostile. I guess even if that is the case the fun “being in love” parts usually outweigh (or at least weigh as much as) the bad parts at the end. I know that logically these fears aren’t valid and that I can’t make those sorts of sweeping generalizations after one failed relationship that wasn’t even all that bad, but there’s a difference between what makes logical sense and what you can’t help yourself from feeling. And it doesn’t help that every time I sit down at my desk at work or get into my car I have to remember to take my stupid gigantic wallet out of my pocket and look at it and remember where it came from and be reminded of my fear of being incompatible with romantic love.

Today I bought a new wallet. It’s light brown and it’s a tri-fold and it’s genuine leather and it isn’t attached to any of my insecurities or fears. And it’s thinner, so maybe it’ll help me to stop ripping all of my goddamn jeans.

Escaping Enemy Territory

In Mark Fisher’s 2013 essay Exiting the Vampire’s Castle, he wraps up his dissection of online political discourse with this description of social media:

We need to think very strategically about how to use social media – always remembering that, despite the egalitarianism claimed for social media by capital’s libidinal engineers, that this is currently an enemy territory, dedicated to the reproduction of capital.

While that sounds like communist nerd shit, he was absolutely correct. A frighteningly prescient take on social media considering the time this was published (November 22, 2013). Twitter had been a publicly traded company for about 2 weeks and Facebook had purchased Instagram about a year and a half prior. Did he know how bad things would get? He would never even get to find out, since he killed himself in 2017. Guess he’d seen enough.

Something about his particular phrase, Enemy Territory, rattles around constantly in my mind. I think about it every time I muscle-memory open the Instagram app on my phone (which is roughly 25 times a day), I think about it when Tiktok feeds me a video that makes me so upset that I spend an extra 40 seconds lamenting in the comments with my fellow algorithm victims, I think about it when my mom tries to show me “the cutest video she’s ever seen” that was generated by a GPU in a data center and prompted by some engagement farming freak. Being bombarded by this thought is not a pleasant feeling. The feeling that I’m relenting to the ever-magnetizing pull of the social media machine. The feeling of their behavioral learning algorithms breathing down my neck while I try to decide as quickly as possible how to engage with the content on my screen so that my experience continues to be tailored correctly. It’s a paranoia, it’s a dull anxiety, it’s the feeling of being behind enemy lines and hardly realizing it. I did not used to feel this.

The day after Mark Fisher published Vampire’s Castle, I turned 13 years old. As a nervous, uncoordinated, and decidedly weird kid, I took every opportunity available to go on the computer. Internet culture was in relative infancy, and hadn’t yet truly breached the mainstream. (I think age 13 was the first time I found a shirt in the mall with a rage comic on it. It was the Troll face, soon followed by the Forever Alone Guy and the Nyan Cat. I had incredible fashion sense.) Little Sam would go home from school every day and log on to his favorite image sharing platforms and see what hilarity had taken place while he was busy learning. It felt like a window into a world that the people around me could not understand, a place where language and jokes and ideas could develop naturally and democratically without the friction and slowness of the physical world. There was a hopefulness and transcendence about it all, logging on wide eyed and full hearted to explore and learn and laugh and enjoy this new world-on-top-of-our-world.

At a certain point I’d come to wonder about and then understand the whole “you’re being advertised to” model of internet moneymaking, and that was fine, I thought. “Of course, the people who are in charge of reddit love the internet and the people that use it, and as it gets more popular, it costs more to keep the machine running. That makes sense!” Or I’d see the oft-regurgitated “If something is free, you’re the product,” taking that only to mean that my favorite internet hangouts could remain free because they were selling real estate on my screen, they were selling the opportunity to sell to me, which didn’t seem all that nefarious. I saw commercials and billboards and ads of all sorts every day, this was just the computer version of that.

How much of my good-faith interpretation was childhood naivety and how much was genuine early-online optimism is impossible for me to say. I’d like to think that I didn’t become too much more cynical and the world really did just get worse, but reading that sentence in the context of my Unabomber-manifesto blog post certainly causes me to lean more to one side. Nevertheless, I never felt as if I was among an enemy of any sort. I felt a sense of community among the geeks and nerds and insufferable gamers. We were slipping under the radar of the mainstream and having all of this fun without any manipulators or bad actors sticking their noses too far into it. At least that’s how it felt.